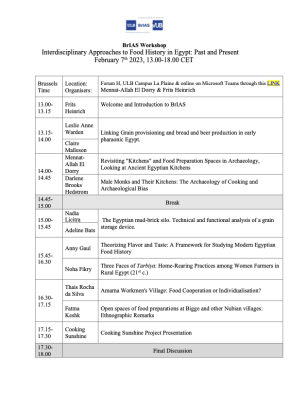

Linking Grain provisioning and bread and beer production in early pharaonic Egypt.

Leslie Anne Warden & Claire Malleson

Abstract.

Studies of bread and beer production have often focused on activities within the bakery, brewery, or kitchen: grinding of grain, making of the mash, baking of the dough. Yet bread and beer were at the heart of many entwined industries and their production rippled out to affect many different activities in Egyptian life. In this paper we seek to investigate the relationship of bread and beer production to two different industries: agriculture and ceramic production. We posit that, through the linkage of bread and beer, the archaeobotanic/ agricultural recordcan inform our questions about the ceramic record - and vice versa.

Dr. Claire Malleson is an assistant professor of archaeology at the American University of Beirut. Since 2007 she has worked as an archaeobotanist, at numerous sites across Egypt. She specializes in the study of ancient Egyptian agriculture.

Dr. Leslie Anne Warden is Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo Associate Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Roanoke College. She directs the excavations of the Kom el-Hisn Provincialism Project (KHPP) at the ancient Egyptians settlement of Kom el-Hisn in the western Nile delta; is the Head of Ceramics Group for the German Archaeological Institute's excavations at Elephantine (directed by Johanna Sigl); and Head Ceramicist at the North Kharga Oasis Survey (directed by Dr. Salima Ikram).

Revisiting "Kitchens" and Food Preparation Spaces in Archaeology, Looking at Ancient Egyptian Kitchens

Abstract

Today's domestic kitchens are, for many, the heart of the household. They are fully equipped spaces with permanently affixed structures. They entail very specific elements altogether in one space: pantry and shelving to store food, countertops to prepare food, heating installations (ovens and toasters etc.) to cook and heat foods, cleaning facilitates (sinks and washing machines), spaces for storing tools (cutlery drawers and perhaps a knife stand). This very modern, and western, image of a kitchen is far removed from traditional kitchens, and certainly from historical and archaeological ones. This paper reconsiders the evidence of domestic "kitchens" from key ancient Egyptian sites, and explores the reasons they were identified as such. Are there recurrent elements which lead archaeologists to propose that these are “kitchens”, and how can “kitchens” be identified at all? In addition to archaeological evidence, texts and artistic representations will also be considered. Ethnohistoric and ethnographic models of modern Egyptian food storage and preparation spaces will further shed light on the often ephermal layout of food preparation spaces, that are often largely furnished with mobile items. The paper will also draw on anthropological discourses on archaeological kitchens.

Mennat-Allah El Dorry is an archaeologist specialized in Egyptian culinary history. She has a PhD in Egyptology with a focus on archaeobotanical analysis. Her research revolves around food and agriculture, exploring how people sourced and prepared food and investigating plant husbandry and trade of agricultural products. She has worked extensively on multiple archaeological sites across Egypt, and has served in a number of positions at the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. She is Lecturer of Archaeobotany at the Faculty of Archaeology at Ain Shams University, and is an associated researcher at the Institut français d’archéologie orientale in Cairo.

Male Monks and Their Kitchens: The Archaeology of Cooking and Archaeological Bias

Darlene Brooks Hedstrom

Abstract

Egyptian Monastic settlements offer a unique body of evidence to examine how communities structured spaces. The sites found throughout Egypt, from the Delta in the north to the edges of the Nile valley, and into the more remote deserts, provide a rich sample of domestic habitations for analysis of where monks built installations for cooking food. I will examine four sites, with unique food preparation areas, to explore whether monastic communities had kitchens and to trace the areas for food preparation. I will also explore the archaeological bias structuring gendered work regarding cooking and whether men participated in food preparation within their monastic communities.

Dr. Darlene L. Brooks Hedstrom, Associate Professor, is the Myra and Robert Kraft and Jacob Hiatt Chair in Christian Studies with a joint appointment in the Departments of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and Classical and Early Mediterranean Studies. She is currently chair of Classical and Early Mediterranean Studies. Brooks Hedstrom is an archaeologist and historian of ancient and early Byzantine Christianity of the eastern Mediterranean world (circa 300-1000 CE) with a specialization in the archaeology and history of monasticism. She is Senior Archaeological Consultant for the Yale Monastic Archaeology Project-North, in Wadi Natrun, Egypt, and a speaker for the Archaeological Institute of America. Her work combines texts, material culture, and theory to examine the history of monastic makers of late antique objects and spaces. Brooks Hedstrom's most recent book, The Monastic Landscape of Late Antique Egypt An Archaeological Reconstruction, is the winner of the Biblical Archaeology Society's Best Popular Book in Archaeology for 2019. She is currently working on an excavation monograph for a monastic residence at the Monastery of John the Little in Wadi Natrun, Egypt. Brooks Hedstrom was a fellow in Byzantine Studies at Harvard University's Dumbarton Oaks for a book project entitled "Feeding Asceticism in Byzantine Monasteries: The Archaeology of Monastic Cooking." In addition, she publishes extensively on late antique Christian archaeology, monasticism, and the history of archaeology.

The Egyptian mud-brick silo. Technical and functional analysis of a grain storage device.

Nadia Licitra & Adeline Bats

Abstract

Mud-brick silos are regularly identified in Egyptian archaeological sites and “daily life” scenes depicted in private tombs since the Old Kingdom. They are present in several types of settlements and associated with various buildings such as temples or more or less modest dwellings. Used for storing of bulk commodities such as cereals, malt, or fruits, these devices were designed to preserve foodstuffs over the medium and long term. In contrast to the grain pit – an underground device well known from the Bronze Age and medieval Europe –, the silo, built in mud-bricks, is mostly cylindrical or conical, domed and provided of a shallow foundation. Although it is still used today in some traditional societies in Africa and the Near East, the storage process is poorly documented and seems to correspond to that of a grain pit. Several hypotheses have been developed through comparisons, but the functioning of this type of construction remains largely unknown.The free-standing silo preserves foodstuff by creating a confined atmosphere, preventing exchanges between internal and external environments. This type of storage protects efficiently the crops against pests but, at the same time, affects the whole processing and consumption of the grain. Assuming that the operation of the mud- brick silo is similar to that of the pit-silo, several questions linked to the long-term conservation of seeds remain and need to be explored further. The first issue concerns the architectural elements: what was the role played by the building materials – essentially mud-bricks, earthen mortars and plasters – and the building techniques in insulating the crops from the outside atmosphere? As a matter of fact, unlike pit-silos, the external atmosphere is much more subject to variations in humidity and temperature than the underground. In addition, how long and how much do seeds retain their germinative properties when stored in a free-standing silo? This question is all the more relevant since, unlike grain pits, Egyptian silos sometimes had to store huge volumes of grain which favours self-combustion and gas emissions. Finally, how the silos were plugged and hermetically closed? In order to answer these questions, a research project was launched in 2021 with the aim of building a mud-brick silo according to the ancient Egyptian building techniques and in collaboration with architects and agronomists. This paper provides a brief update on the literature and presents the implementation and the results of this experimental research project.

Nadia Licitra is an archaeologist, post-doc fellow at CRAterre (AE&CC/ENSAG/UGA) and associated member of UMR 8167 Orient&Méditerranée of CNRS. She obtained her PhD degree in Egyptology in 2014 (Paris-Sorbonne University) and since 2008 she has been the Director of the archaeological mission at the Treasury of Shabaqo in Karnak (UMR 8167/CFEETK). She has taken part in several archaeological missions in Italy, Egypt and Sudan. Her research focuses mainly on storage architecture, construction techniques and materials of Nile valley earthen architecture. In 2020, Adeline Bats and Nadia Licitra created a Research group on Storage in ancient Egypt and Sudan with the aim of further exploring this subject and bringing together scientists from different backgrounds: archaeologists, historians, architects, ethnoarchaeologists and agronomists. (http://stockagenil.hypotheses.org).

Adeline Bats holds a PhD in Egyptology from the University of Paris Sorbonne. She has been involved in the archaeological site of Ayn Sukhna (IFAO/UMR 8167) since 2014 and Ouadi el-Jarf (IFAO/UMR 8167) since 2015, where she is archaeologist and ceramologist. She also joined the archaeological Franco-Swiss-Sudanese mission of Kerma-Doukki Gel in 2021. She defended her thesis entitled “Les céréales et les produits céréaliers au Moyen Empire. Histoire technique et économique” in 2019 under the direction of Pierre Tallet and Juan Carlos Moreno García. In this work, she aimed to understand the role of cereals in Pharaonic society in human and animal nutrition through a technical approach. She then proposed a socio-economic analysis, integrating textual, archaeological, and economic anthropological data. During her PhD, she trained in experimental archaeology and conducted several experiments on bread baking in conical moulds.

Theorizing Flavor and Taste: A Framework for Studying Modern Egyptian Food History

Anny Gaul

Abstract

This paper outlines a theoretical framework for writing the cultural history of a central phenomenon in Egypt’s modern domestic cuisine: the transformation of the tomato from foreign flora to everyday staple (provisional title: Nile Nightshade: Tomatoes and the Making of Modern Egypt). It also includes a discussion of the sources and methods used to apply this framework. The three cornerstones of my theoretical framework address the nation, gender, and affect in turn. To explore these concepts and explain how they relate to one another, I use a methodology that I call “kitchen history”: a way of doing history that takes into account the vernacular, the domestic, and the affective. First, I build on the work of feminist theorists of the domestic sphere (e.g., Kaplan 2002; Stoler 2002) to propose a specific approach to the domestic that considers it not merely a space where gendered norms were defined, but also as a space where the national was defined against the foreign. Next, I outline the need to integrate vernacular understandings of the domestic sphere into discussions of the nation. I suggest that a national cooking style emerged as a vernacular idiom that was central to the way that Egyptians identified themselves and one another as Egyptian. Finally, I outline a new approach to the study of this newly framed and conceptualized domestic realm. I suggest that the home kitchen in particular invites us to think of national and regional categories like Egyptian and Mashriqi as structures of feeling (Williams 1977) in continuous formation, rather than as fixed entities. I do this with a methodology that considers the history of cultural material that is sensed, embodied, and felt in addition to what is written and uttered. Doing so entails distinguishing between the “official consciousness” that is often expressed via discourses of taste and the “practical consciousness” by which home cooks produce specific flavors.

Anny Gaul is a cultural historian of food and gender in the Arabic-speaking world. She is currently an assistant professor of Arabic Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research has been published in Global Food History, Gender & History, and the Journal of Women's History, among others. She is the co-editor of Making Levantine Cuisine: Modern Foodways of the Eastern Mediterranean (University of Texas, 2021) and is currently writing a book about the history of the tomato in Egypt. You can follow her cooking and research on her blog, Cooking with Gaul.

Three Faces of Tarbiya: Home-Rearing Practices among Women Farmers in Rural Egypt (21st c.)

Noha Fikry

Abstract

Prevalent in weekly markets in Egypt are rural home-reared animals, which are more expensive and preferred than industrially grown and imported meats. The value of these home-reared animals is described through “tarbiya”, an Arabic word referring to the practice of rearing animals, but also raising and disciplining human children (see Fikry 2022). Intrigued by tarbiya, this ethnographic research explores the livelihoods, local ecologies, and human-animal relationships of women farmers rearing animals in their homes in rural Egypt. These animals include chickens, goats, and rabbits, and are kept on rooftops, in courtyards, or in shared open enclosures. To understand the meanings of home-rearing practices and the value of home- reared animals, I ask: (1) What are the social/material relations through which an animal becomes meat among women farmers in rural Egypt? (2) What does tarbiya do to an animal and how does it describe the taste of the animal as it is turned into meat? (3) What is the relationship between caring for and killing animals in tarbiya and how do religious slaughtering rules facilitate these nodes of human-animal relations? (4) Is tarbiya a strictly gendered, feminized, undertaking? (5) What is the role of hospitality in rearing animals that become meals to guests in rural Egypt? In this essay, I attempt to trace different uses of tarbiya and make a case for tarbiya as both a concept and a methodological tool that attends to the more-than- human and gastronomic components of this research.

Noha Fikry is a PhD student in anthropology with a specialization in food studies at the University of Toronto. She is interested in human-animal relations, food, and hospitality. She is also interested in narrative tools, ethnographic writing, and experimental writing. Noha's PhD research explores home-rearing practices among women farmers in rural Egypt, particularly how women negotiate caring for, killing, cooking, eating, and selling food animals.

Amarna Workmen's Village: Food Cooperation or Individualisation?

Thais Rocha da Silva

Abstract

The Amarna Workmen’s Village is a special purpose settlement that housed the workforce engaged in the royal construction projects. The settlement was occupied for approximately 20 years and its inhabitants likely had to finish their homes after the Egyptian administration laid out the building area. Archaeological evidence from the village shows that people engaged in many modifications within their houses, adding or removing walls and building installations for food production. This evidence has been investigated mainly from an economic perspective. Delwen Samuel’s work about bread making in the village emphasized a process of individualisation in which the inhabitants were operating independently of one another. She argued that the presence of the state and the dependence on state provisions led the local population to be less cooperative. In this paper, I explore a different venue, arguing instead that the village privileged cooperation for food production. Domestic maintenance activities should not be regarded simply to an economic, utilitarian perspective. Rather, daily life in the Workmen’s Village was subject to specific type of domestic experience that were not solely based on individual houses, but the village itself.

Thais holds a PhD in Egyptology from the University of Oxford. She is now Visiting Research Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Postdoc at the University of São Paulo, and Research Fellow at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford. Her current research focuses on ancient Egyptian settlements during the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BCE), combining archaeological and anthropological approaches to material culture and houses. Thais is interested in the intersection of institutional and individual’ lives and how material culture constitutes social practices within the domestic sphere. She is part of the Amarna Project in Egypt and co-directs the project Being Egyptian together with Dr Linda Hulin, with the collaboration of the Egypt Exploration Society. Link: https://www.thaisrocha.net/

Open spaces of food preparations at Bigge and other Nubian villages: Ethnographic Remarks

Fatma Keshk

Abstract

Shared spaces of food preparation were uncovered in Old Kingdom Giza settlement of Heit el Ghorab by the AERA team. Similar spaces have probably their evidence at Middle Kingdom Elephantine quarters. Until today in the rural villages of Egypt, food preparation steps prior to food cooking can take place in the open spaces inside or outside houses. Ethnographic research has shown that many of the open spaces in between houses are in most of the cases shared spaces between neighbors that are used as shared food preparation spaces. In the village of Bigge, ethno-archaeological research confirmed this utility of open spaces, based on the available material culture and ethnographic research. This contribution aims to discuss examples of food preparation spaces from the village of Bigge, Aswan and proposes a methodology to study these spaces in ancient Egyptian settlements.

Fatma Keshk is an Egyptologist, heritage outreach expert and storyteller. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the IFAO and the PCMA. Keshk's research concentrates on the study of domestic open spaces through ethno-archaeological approaches and also on contemporary Egyptians' perceptions of history and reconstructing the unknown history of Egyptian Egyptology. Working with local communities has allowed her to explore the overwhelming richness of Egyptian heritage, its perception and how it can be regenerated through and for its people. Her award-winning first published story A Tale of Shutb documenting the heritage of Shutb village was produced within the framework of the British Museum Project at Shutb.

Cooking Sunshine Project Presentation

Mina Nasr and Lamis Haggag

In December 2022 we took part in a research-based artist residency at Fekra cultural center in Aswan, Egypt. We were researching local traditional dishes that were either dried, fermented or cured in the sun. We chose Aswan as it is the sunniest city in Egypt and the 2nd sunniest in the world. In addition to the fact that the locals are rarely incorporated in collaborations in the Arts in Egypt. During our stay, we researched and documented the ancient techniques of solar cooking, the recipes as per our ancient traditions and built our own solar cooking device. The Host organization in Aswan, “Fekra Cultural Center” supported our project by providing us with crops from their land and facilitating a cultural exchange with the local people. Starting with the sun bread, a bread that is still baked and widely consumed in upper Egypt and moving on to other recipes that contained meat, veggies and drinks. The result of our stay, in Aswan, consisted of a series of dinner and lunch invites and workshops for the community around Fekra. As a means to encourage the community to use alternative cooking mechanisms as sustainable methods for preparing their meals. We have also been working on an artist cookbook that combines the different recipes. In an attempt to revive traditional recipes and bring attention to crops and other local foods during their seasons in Egypt, as opposed to importing crops throughout the year.

Mina Nasr and Lamis Haggag are an Egyptian artist duo that came together in 2022. Nasr has completed his Bachelor of Applied arts From Helwan University Egypt and did his Fulbright research grant in Art and Social Justice at Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, George Washington University, D.C., USA. While Haggag has received an MFA from the University of Calgary, Canada and a BFA from Helwan University in Egypt. Both artists have participated in artistic Events in Europe, North America, Asia, as well as other African countries and have received recognition and grants both locally and internationally.